Improvisation is one of the most complex forms of creative behavior. The improvising musician faces the unique challenge of managing several simultaneous processes in real-time – generating and evaluating melodic and rhythmic sequences, coordinating performance with other musicians in an ensemble, and executing elaborate fine-motor movements – all with the overall goal of creating esthetically appealing music. (Beaty, 2015)

A JAZZ MUSICIAN’S STRESS STORY

Billy is a great jazz musician that has a regular concert date on Saturday nights in a jazz club of his small native town. The music is ready for performance, he’s playing at his best (as usual), his bandmates are in a good mood and people in the audience are having a great time. In the middle of the 2nd set, another musician enters the venue. He’s a fantastic, really well-known musician from outside town. He finds his way through the crowd and sits right in front of the stage, first row. From the stage, Billy recognizes him, of course. He says to himself:” Hey, that’s Kenny Watson from New-York… I think he was playing tonight in the concert hall with his band. Wow!! this guys is so great!” So while deciding on the next tune, he starts feeling his heart beating faster and louder, his breathing speed has increased, he has dry mouth and his hands start to shake a bit. First of all, he counts off the piece (a bit too fast…), then BOOM, memory blank—He forgets parts of the melody. He starts improvising, but after a chorus or two, he gets lost in the form. While wanting to get back on track, he feels that he can’t because he forgot the chord changes. A feeling of confusion, fear and insecurity takes him over. All that time, the music is playing but he feels like he is outside of it, like as if he was in a completely different place and time frame. Confused, he finally stops playing in the middle of the bridge section, forcing the piano player to abruptly take over.

After the show, the piano player comes to him and asks: “Hey, what happened in that tune we played? You were doing so well all night, and all of a sudden, you seemed to have lost it.” The answer to that question was: “I don’t know…”

Even though he usually stays at the venue to talk to people he knows, he quickly packs up his gears and leaves. On his way home, he bumps into one of his long time friend who asks him about the performance: “So, how did the gig go tonight??”

He answers: “It went so bad… I’m the worst player on the planet, I can’t play anymore. I think I should quit…”

Looking at the situation,it is obvious that stress interfered with Billy’s capacity to improvise fluently, but how exactly?

[accordion multiopen=”true”]

First, let’s take a look inside the improviser’s mind.

[toggle title=”What’s happening in a musician’s mind during improvisation?” state=”open”]

PRESSING’S MODEL OF IMPROVISATION

Pressing’s model of improvisation seems to be one of the most accurate in the literature so far. In fact, most of the research done to this date tends to acknowledge it. In 2015, Beaty wrote the review The neuroscience of musical improvisation and summarized it in his introduction.

Pressing’s model of improvisation seems to be one of the most accurate in the literature so far. In fact, most of the research done to this date tends to acknowledge it. In 2015, Beaty wrote the review The neuroscience of musical improvisation and summarized it in his introduction.

Improvisation is an acquired skill that requires a lot of practice to be mastered (about 10000 hours over a 10-year period, also known as the 10-year rule). It is stated that it involves an interplay between cognitive, perceptual and emotional referent processes (a series of well-rehearsed retrieval cues that are deployed during performance, minimizing processing demands and guiding idea generation) and procedural and declarative information stored in a domain-specific knowledge base (hierarchical knowledge structures stored in long-term memory). Also, Pressing includes the perceptual feedback, short-term (ongoing motor movement) and long term (decision making and response selection), and error correction, that allows the improviser to minimize the distance between intended and actual performance. (Beaty, 2015)

In fact, the close-loop model Pressing proposes includes the feedback in the creative process, as the improviser is comparing the actual output with the intended output, and then adjusting the future performance. He conceptualized improvisation as a series of generative and evaluative processes. Although these processes involve some level of cognitive control and conscious monitoring, Pressing emphasizes the role of automatized motor processes and routines (e.g., well-rehearsed action sequences) and argues that improvisational fluency relies on automatized processes that require minimal conscious attention. (Beaty, 2015)

“Domain-specific expertise seems especially relevant to musical improvisation. In addition to the physical and psychological constraints common to other domains of skilled performance, jazz musicians must perform under extraordinary temporal constraints. Improvising requires the simultaneous execution of several processes in real-time, including sensory and perceptual encoding, motor control, performance monitoring, and memory retrieval, among others.” (Beaty, 2015)

[/toggle]

Let’s now investigate stress, and see how it can interfere with the musician’s improvisational capacities.

[toggle title=”An overview of stress” state=”open”]

“Stress refers to an organism’s physiological and psychological reaction triggered by an external or internal stressor, such as an environmental condition or a psychological stimulus. It is a state of mental or emotional strain or tension resulting from adverse or demanding circumstances and can last for just a few minutes to hours (acute stress) up to months or even years (chronic stress).” (Ness & Calabrese, 2016)

“Stress refers to an organism’s physiological and psychological reaction triggered by an external or internal stressor, such as an environmental condition or a psychological stimulus. It is a state of mental or emotional strain or tension resulting from adverse or demanding circumstances and can last for just a few minutes to hours (acute stress) up to months or even years (chronic stress).” (Ness & Calabrese, 2016)

So, what makes us stressed out? What characteristics make a situation stressful?

According to the N.U.T.S. theory, a stress response in human can be triggered if one or more of the following characteristics are present in any given situation. The more elements present, the more chances there is for an individual to experience stress. They are: Novelty, Unexpectability, Threat to the ego and the lost of Sense of control over a situation.

OK, a situation is perceived as stressful by the brain… Then, what happens in the body??

As pointed out by Ness and Calabrese (2016), when a situation is perceived as stressful, neurons located in the periventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus synthesize and release corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) which in turn triggers the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary gland into the bloodstream. ACTH acts on the adrenal glands and thus induces the release of glucocorticoids from the adrenal cortices. Glucocorticoids alter the function of multiple body tissues in order to mobilize or store energy to meet the demands of a stress challenge.

This stress system is called Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis (also called HPA axis)

There are two main classes of stress hormones: the glucocorticoids, also called cortisol in human, and catecholamines, also known as epinephrine and norepinephrine. Once those hormones are released, they bind to two types of receptors at different location in the body. First, the low-affinity mineralocorticoid receptors, situated almost exclusively in the hippocampal formation, and secondly, the high-affinity glucocorticoid receptors which are present in high concentrations in the hippocampus, the amygdala, and the prefrontal cortex. (Ness & Calabrese, 2016)

“In a resting state, the mineralocorticoid receptors are usually occupied, while the glucocorticoid levels are too low to bind to the low-affinity glucocorticoid receptor. When a stressful event occurs, glucocorticoid level gets high enough to activate both low-affinity and high-affinity receptors” (Ness & Calabrese, 2016). It is then that stress symptoms may be experienced.

Here’s a short explanatory video on the topic:

So, what symptoms does stress create on the human body?

They can be categorized as follows (Kenny, 2011):

- SOMATIC (Physiological): Symptoms including muscle tension, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, cold hands, tremors, dry mouth, cold sweat…

- AFFECTIVE (Emotional): Symptoms like feeling of confusion, panic, insecurity, fear, worries, guilt…

- COGNITIVE: Can include memory slips, inability to focus, decrease concentration, narrowing of attention …

- BEHAVIORAL (That other people can assess too): impaired coordination, trembling, fidgeting, social avoidance…

[/toggle]

In musical improvisation, as in any complex cognitive task, the control of attention is a key factor for success. But, what is attention? How does it work? Does stress have any effect on it?

[toggle title=”An overview of attention” state=”open”]

Attention is something really difficult to define. During the course of history, a lot of different definitions have been given to it. Here’s one of them: “Attention is conceptualized as the capacity to focus on particular stimuli over time and to manipulate flexibly the information.” (Sohlberg & Mateer 1986)

Attention is something really difficult to define. During the course of history, a lot of different definitions have been given to it. Here’s one of them: “Attention is conceptualized as the capacity to focus on particular stimuli over time and to manipulate flexibly the information.” (Sohlberg & Mateer 1986)

A clinical model of attention

- Focused attention: The ability to respond discretely to specific visual, auditory or tactile stimuli.

- Sustained attention: The ability to maintain a consistent behavioral response during continuous and repetitive activity

- Selective attention: The ability to maintain a cognitive set in which requires activation and inhibition of responses dependent upon discrimination of stimuli.

- Alternating attention: Capacity for mental flexibility which allows for moving between tasks having different cognitive requirements.

- Divided attention: The ability to respond simultaneously to multiple tasks.

Here are three explanatory videos on attention models and theories:

[tabs]

[tab title=”Attention”]

[/tab]

[tab title=”Theories of selective attention”]

[/tab]

[tab title=”Attention and multitasking”]

[/tab]

[/tabs]

Different attention types:

- Internal Attention (endogenous): selecting information that is already represented in the mind, recalled from long-term memory or being maintained in working memory.

“Internal attention includes cognitive control processes and operates over representations in working memory, long-term memory, task rules, decisions, and responses. It is the set of operations that are focused on such cognitive representations.” (Chung, Golomb & Turk-Browne, 2011)

- External Attention (exogenous): Observation of stimulus through the senses (outside of the self).

“Attention can be directed to one or several modalities (e.g. the five senses), separable from each other during initial neural processing. Independent of modality, attention is deployed over space and over time, with separate issues to consider for spatial versus temporal attention. In addition, attention can be allocated over space, time, and modality according to stimulus features or how they are organized into objects”(Chung, Golomb & Turk-Browne, 2011).

Different attentional styles (Williamon, 2004):

- Broad/external: Observation of a wide range of stimuli outside of the self.

- Broad/internal: Observation of a wide range of sensations, feelings, thoughts within the self.

- Narrow/internal: Focusing attention on specific sensations, feelings and thoughts within the self.

- Narrow/external: Focusing on specific events and stimuli outside of the self.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Effects of stress and emotional arousal on attention:” state=”closed”]

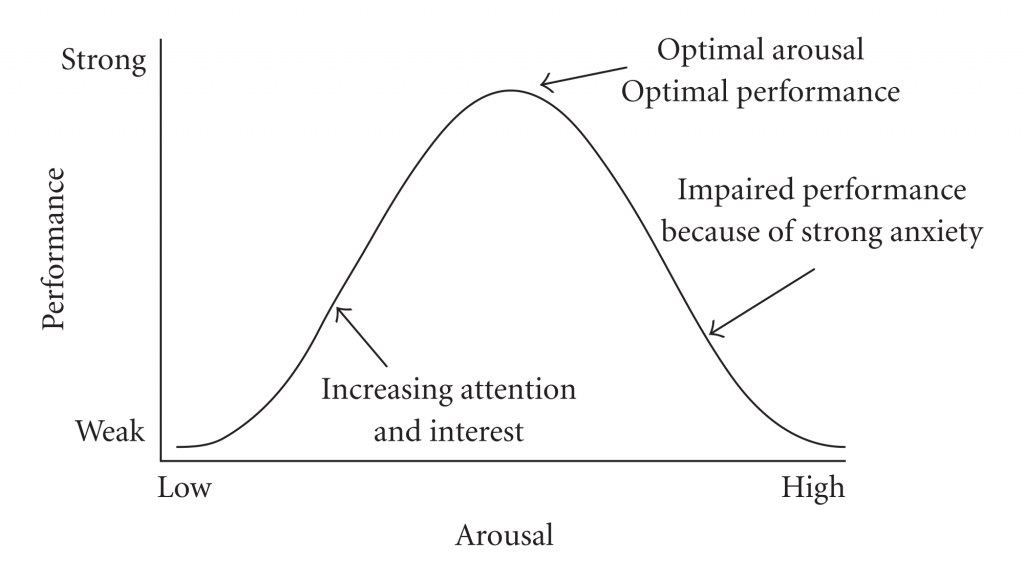

Arousal and performance are linked together by the Inverted-U shape diagram. If the arousal level is too low or too high, it will affect the performance negatively. The optimal performance zone (the optimal arousal level to complete a certain task) is different for everybody.

Stress can have a positive effect on attention if it does not go beyond a certain level. If it does, the effects can be debilitating.

Findings showed that a high level of stress can create attentional narrowing which is the involuntary reduction in the range of cues that can be utilized by an individual. (Prinet & Sarter, 2015) Also, impairments in different attention tasks were detected in participants with high stress level and emotional arousal (i.e. Hancock & Warm, 1989, Heckens et al., 2012, Olver et al., 2015). Under stress, the attention automatically seeks for threatening stimuli, drifting away from the task at hand. It is therefore more difficult to stay focused on the same stimulus for a long period of time.

The act of improvising within an ensemble is an even more complex task, since communication comes into play. The musician is not only creating his own musical fragments, but also reacting to other people’s musical ideas. A situation like this requires a great amount of attention, employing all fives types of attention outlined in the clinical model. During a concert, they are all used, at one time or another, to achieve an optimal performance.

Improvising also seems to require both attentional types: external, (in order to stay aware of as many auditory and visual cues as possible given by other band members, for example) and internal (to remember previously played melodies and rhythm and developed them while soloing, to think of different combination of melodic fragments, etc.). But in both types, the broad attention style tends to make the improvising musician more successful, since there’s less discrimination of specific sounds or feeling, which will put the musician into a “wide open” optimal receptive type of mindset.

As mentioned earlier, studies on the impact of stress on attention show an impairment in the focused, sustained, selective, and divided categories of the model. (Olver et al., 2015) Also, results showed to be associated to an attentional narrowing. (Prinet & Sarter, 2015) The fact that the stressed musician’s attention will tend to drift towards the threatening stimuli will distract him from the task at hand (e.g. musical improvisation), therefore resulting in an impaired musical performance.

[/toggle]

In addition of attention, memory plays a great role in improvisation fluency. In fact, what is memory? In what way can it be affected by stress?

[toggle title=”An overview of memory” state=”open”]

The Oxford dictionary defines memory as being the faculty by which the mind stores and remembers information.

The Oxford dictionary defines memory as being the faculty by which the mind stores and remembers information.

According to Baddeley, memory is an informational processing system in three parts: the sensory processor, the working memory and the long-term memory.

- Sensory processor allows information from the outside world to be sensed in the form of chemical and physical stimuli and attended to with various levels of focus and intent.

- Working memory serves as an encoding and retrieval processor. Information in the form of stimuli is encoded in accordance with explicit or implicit functions by the working memory processor. The working memory also retrieves information from previously stored material. It has a pretty limited capacity: maximum storage is 7 +/- 2 items at a time. Baddeley’s model of working memory includes three components: The visuospatial sketchpad, the central executive and the phonological loop.

- Long-term memory stores data through various categorical models or systems.

Different memory systems within the long-term memory and where their processing occurs in the brain:

Declarative memory allows for encoding the relationships between multiple items and events, it is considered to be representational, hence providing an internal model of the external world which is either true or false. It is divided in two systems: semantic (facts) and episodic (events) memory. “Both of these declarative memory systems critically rely on brain structures in the medial temporal lobe (e.g., hippocampus) and the diencephalon. Additionally, other brain structures, such as the prefrontal lobe, also participate in episodic memory processes.” (Ness & Calabrese, 2016)

Non-declarative memory contents are not subject to conscious recollection, are not representational, and are thus neither true nor false. It is further divided into four subsystems, which are responsible for functionally distinct processes (Ness & Calabrese, 2016):

- procedural/habit memory: Refers to skill based and largely automatic processes and is dependent on the striatum.

- priming/perceptual learning: The phenomenon of an increased likelihood of re identifying a previously subconsciously perceived stimulus/item, which is regulated by the neocortex.

- conditioning: involves the amygdala and the cerebellum.

- non-associative learning: operates over reflex pathways.

Here’s an explanatory video on the topic.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Effects of stress on memory” state=”closed”]

In their 2016 review, Ness & Calabrese reported that stress and emotional arousal can affect memory both on quantitative (that is time-dependent) and qualitative aspects.

Memory encoding process vs memory retrieval process.

The authors report that studies on quantitative memory performances have been focusing mostly on hippocampus-dependent. It has been found that stress as time-dependent effects of the stressor on encoding, consolidation, and retrieval. A stressor occurring just before or after the encoding process might have an enhancing effect on it (Abercrombie, Speck & Monticelli, 2006). Also, in periods of higher stress and emotional arousal, the memorization of negative information is enhanced while the neutral information memorization seems impaired. As far as the retrieval phase, the authors wrote that, generally speaking, in high emotional arousal and high stress situation an impairment has been shown. Researchers also found that emotional arousal is essential to impairment, since pharmacologically-induced increases in glucocorticoid levels do not impair memory retrieval in a non-arousing situation.

In general, a physiological stress response is beneficial when occurring during the learning episode but impairs memory function when experienced during retrieval.

Hippocampus-dependent cognitive memory vs striatum-dependent habit memory: A competitive relationship.

Stress and emotional arousal affects the memory processing mode. In fact, a competitive relationship between cognitive and habit memory seems to be in place. Along that line, a study by Schwabe & Wolf (2012) has shown that in presence of stressors, people tend to switch from the declarative hippocampal strategy to the non-declarative striatum-based strategy. In that same  review, Ness & Calabrese wrote that findings suggest that the preference for striatum-dependent habit learning strategies under stress appears to be a result of both enhanced habit memory and impaired cognitive memory. It can be concluded that a shift from cognitive to habit memory systems under stress can rescue task performance and the attempt to engage the declarative memory system during the experience of stress event disrupts task performance.

review, Ness & Calabrese wrote that findings suggest that the preference for striatum-dependent habit learning strategies under stress appears to be a result of both enhanced habit memory and impaired cognitive memory. It can be concluded that a shift from cognitive to habit memory systems under stress can rescue task performance and the attempt to engage the declarative memory system during the experience of stress event disrupts task performance.

In an improvised music setting, if retrieval process is impaired by stress, it is quite obvious that the quality of the performance will suffer. According to Pressing’s improvisation model, memory retrieval of pre-learned cues is essential to improvisation fluency. If those bits of information are not known enough by the performer, there is a good chance that he will forget about them when the stress situation comes up. As mentioned above, the habit memory is generally taking over the cognitive memory in stressful situations. A conclusion can be made that the musician will tend to play his habitual language, instead of being able to react to sounds that are made in the moment.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”So, does stress has any other effects on the improvising musician?” state=”open”]

Other symptoms can interfere with the quality of the improvised performance. The cognitive aspect was our general focus here, but the somatic, affective and behavioural symptoms can definitely interfere with an optimal performance. For example, a trombone player, or any other instrumentalist, needs to be in perfect control of his instrument in order to improvise freely. To achieve this, he will need to (1) control the air stream that make his lips vibrate to produce the desired sound, (2) have fine motor control over the muscles implied in his embouchure, (3) control the fine movements of the tongue for subtleties in the articulation, (4) to control the movement of his right arm in order to move smoothly from position to position and (5) coordinate all those elements together to be able to play the musical fragment that he hears in is mind, without any score or visual support. So symptoms that are not necessarily in the cognitive category like, dry mouth, muscular tension, tremor, respiratory problems, lack of fine motor control or lost of muscular coordination for example, may have an impact on the quality of the performance.

Other symptoms can interfere with the quality of the improvised performance. The cognitive aspect was our general focus here, but the somatic, affective and behavioural symptoms can definitely interfere with an optimal performance. For example, a trombone player, or any other instrumentalist, needs to be in perfect control of his instrument in order to improvise freely. To achieve this, he will need to (1) control the air stream that make his lips vibrate to produce the desired sound, (2) have fine motor control over the muscles implied in his embouchure, (3) control the fine movements of the tongue for subtleties in the articulation, (4) to control the movement of his right arm in order to move smoothly from position to position and (5) coordinate all those elements together to be able to play the musical fragment that he hears in is mind, without any score or visual support. So symptoms that are not necessarily in the cognitive category like, dry mouth, muscular tension, tremor, respiratory problems, lack of fine motor control or lost of muscular coordination for example, may have an impact on the quality of the performance.

At the end of our introductory story, the answer of our stressed musician to the piano player’s question could have been different. One hypothesis could be that seeing this intimidating musician coming in the venue triggered a stress response, probably due to the T part of the N.U.T.S stress theory, the threat to the ego, as he was fearing negative judgement. The H-P-A axis went on and glucocorticoids were released by the adrenal glands. The different effects of stress hormones on tissues made him suffer from somatic, behavioral, affective and cognitive symptoms of stress. As he lost track of the form, sustained and focused attention were impaired. Memory retrieval was also impaired, as he forgot parts of the melody and the chord changes, leaving him helpless in the middle of, what HE felt was, sound chaos. Feelings of worry, shame and guilt haunted him after the performance, as he got back home.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”What can be done to prevent this to happen?” state=”open”]

First, stress management strategies can be adopted to minimize the stress response. Studies show that the practice of mindfulness meditation (Kenny, 2011), pranayama breathing techniques (Pal, Velkumary, & Madanmohan, 2004) or progressive muscular relaxation (Williamon, 2004) exercises can have a positive impact on reducing stress. Common sense suggests that a healthy way of living, good and balanced nutrition with regular and sufficient water intake, regular moderate exercising and good sleeping habits have, in general, a positive impact on stress management.

First, stress management strategies can be adopted to minimize the stress response. Studies show that the practice of mindfulness meditation (Kenny, 2011), pranayama breathing techniques (Pal, Velkumary, & Madanmohan, 2004) or progressive muscular relaxation (Williamon, 2004) exercises can have a positive impact on reducing stress. Common sense suggests that a healthy way of living, good and balanced nutrition with regular and sufficient water intake, regular moderate exercising and good sleeping habits have, in general, a positive impact on stress management.

Attention too can be practiced. Attention style exercises, meditation and breath counting for example are proven to increase the capacity of switching types and styles over time. (Williamon, 2004)

Knowing that, in stressful situations, the habit memory is taking over the cognitive memory can orient practice sessions toward the transfer of the information into the non-declarative memory system. The use of the different attentional types to enhance encoding and consolidation could be a good avenue for further exploration.

Finally, changing our attitude toward stress and seeing it as a positive feeling (to some extent) can help. As seen above, in the right amount, emotional arousal can enhance information encoding and can put the performer in the optimal performance zone. It can be perceived as excitement and can bring joy and happiness to the person experiencing it.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”References” state=”closed”]

Abercrombie, H. C., Speck, N. S., & Monticelli, R. M. (2006). Endogenous cortisol elevations are related to memory facilitation only in individuals who are emotionally aroused. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 31, 2, 187-196. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.06.008

Baddeley, A. (2003). Working memory and language: an overview. Journal of Communication Disorders, 36, 3, 189-208. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1016/S0021-9924(03)00019-4

Beaty, R. (2015) The neuroscience of musical improvisation. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 51, 108-117. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.01.004

Chun, M. M., Golomb, J. D., & Turk-Browne, N. B. (2011). A Taxonomy of External and Internal Attention. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 1, 73-101. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100427

Gagnon, S. A., & Wagner, A. D. (2016). Acute stress and episodic memory retrieval: neurobiological mechanisms and behavioral consequences. Annals- New York Academy of Sciences, 1369, 1, 55-75. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12996

Hancock, P. A., & Warm, J. S. (1989). A dynamic model of stress and sustained attention. Human Factors, 31, 5, 519-37. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/001872088903100503

Henckens, M. J. A. G., van, W. G. A., Fernandez, G., Henckens, M. J. A. G., Joels, M., van, W. G. A., & Fernandez, G. (2012). Time-dependent effects of cortisol on selective attention and emotional interference: A functional MRI study. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 6.

Hoehn-Saric, R., & McLeod, D. R. (2000). Anxiety and arousal: physiological changes and their perception. Journal of Affective Disorders, 61, 3, 217-224. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00339-6

Kenny, D. T. (2011). The psychology of music performance anxiety. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lupien, S. J., Maheu, F., Tu, M., Fiocco, A., & Schramek, T. E. (2007). The effects of stress and stress hormones on human cognition: Implications for the field of brain and cognition. Brain and Cognition, 65, 3, 209-237. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1016/j.bandc.2007.02.007

Lupien, S. J., & McEwen, B. S. (1997). The acute effects of corticosteroids on cognition: integration of animal and human model studies. Brain Research Reviews, 24(1), 1-27. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1016/S0165-0173(97)00004-0

MacLeod, C., & Mathews, A. (1988). Anxiety and the allocation of attention to threat. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. A, Human Experimental Psychology, 40, 4, 653-70. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14640748808402292

Mendl, M. (2000). Performing under pressure: stress and cognitive function. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 65, 3, 221. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1016/S0168-1591(99)00088-X

Ness, D., & Calabrese, P. (2016). Stress Effects on Multiple Memory System Interactions. Neural Plasticity, 2016, 3, 1-20. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/4932128

Olver, J. S., Pinney, M., Maruff, P., & Norman, T. R. (2015). Impairments of Spatial Working Memory and Attention Following Acute Psychosocial Stress. Stress and Health, 31, 2, 115-123. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smi.2533

Pal, G.K., Velkumary, S. & Madanmohan (2004). Effect of short-term practice of breathing exercices on autonomic fonctions in normal human volonteers. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 120, 2, 115-121.

Pressing, J. (1988). Improvisation: Methods and models In J. A. Sloboda (ed.) Generative processes in music: The psychology of performance, improvisation, and composition. Oxford [England: Clarendon Press. doi: http://10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198508465.003.0007

Prinet, J. C., Sarter, N. B., & 59th International Annual Meeting of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, HFES 2014. (2015). The effects of high stress on attention: A first step toward triggering attentional narrowing in controlled environments. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 1530-1534.

Schwabe, L., & Wolf, O. T. (2012). Stress modulates the engagement of multiple memory systems in classification learning. The Journal of Neuroscience : the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 32, 32, 11042-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1484-12.2012

Sohlberg, M. K. M., & Mateer, C. A. (1987). Effectiveness of an attention-training program. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 9, 2, 117-130. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01688638708405352

Wen, Z. (2012). Working memory and second language learning. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 22, 1, 1-22. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2011.00290.x

Williamon, A. (2004). Musical excellence: Strategies and techniques to enhance performance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wolf, O. T. (2009). Stress and memory in humans: twelve years of progress?. Brain Research, 1293, 142-54. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1016/j.brainres.2009.04.013

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Images” state=”closed”]

Piano via pixabay.com

https://pixabay.com/en/music-keyboard-classic-acoustic-1887114/

Stressed man via pixabay.com

https://pixabay.com/en/man-stress-male-face-adult-young-742766/

Focus via pixabay.com

https://pixabay.com/en/lens-camera-lens-focus-focusing-1209823/

Yerkes-Dodson Law curve via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HebbianYerkesDodson.svg

Memory via pixabay.com

https://pixabay.com/en/recordings-memory-unconscious-2117786/

Elephant fight via pixabay.com

https://pixabay.com/en/elephant-mammals-wild-animals-624127/

Question marks via pixabay.com

https://pixabay.com/en/road-sign-attention-right-of-way-63983/

Stop sign via pixabay.com

https://pixabay.com/en/stop-shield-traffic-sign-road-sign-634941/

[/toggle]

Leave a Reply